With absenteeism eating away at the city’s public schools the district has begun to seriously examine the problem using data to find possible solutions. “You do have a pretty serious attendance issue,” said Hedy Chang, a student attendance expert, who will sift through the data to find solutions to address the problem. “The good news is this is a solvable issue,” said Chang, who runs Attendance Works, an initiative that views chronic absence as a major obstacle that holds students back.

“Half of the population of our 3 to 4 year olds are not chronically absent, and that’s good,” said Susan Peron, director of the district’s early childhood education, while displaying a series of graphs and charts. “Half of our population is somewhat nearing chronic absenteeism.”

During the first year of preschool almost half of the students had an attendance problem, according to data obtained for school year 2012-13 from the city’s school district. 49-percent of first year preschoolers were chronically absent, defined as missing more than 10-percent of school days. 51-percent of students managed to consistently attend pre-school. Peron stressed that preschool prepares children for kindergarten and without it students begin with a disadvantage. “It really is the beginning of school,” said Peron.

Chang took three members of the audience during Thursday’s community forum on attendance at Eastside High School auditorium to demonstrate how students fall behind as a result of chronic absences.

One student, as she demonstrated, attended every single preschool classes, and he was ahead, prepared for kindergarten. A second student, who missed some classes but attended others, was less prepared and learned less as a result. A third student, who was chronically absent, gradually fell behind with every absence. “The car started breaking down,” said Chang, explaining one of the many reasons a preschooler might not show.

“It’s not just each of the day she missed, but then when she came back the next day, she couldn’t figure out what was going on in the classroom,” said Chang, while showing how one of the three fell very far behind academically. Children starting school for the first time sometime fall ill as a result of being exposed to other germy children, said Chang, resulting in high absenteeism during first year of preschool.

During the second and third year of preschool the rate improved: 63-percent attended without missing more than 10-percent of school days. Chronic absence declined to 37-percent. The improvement can be attributed to second and third year preschoolers being more suited and adapted to their germ-filled school environments.

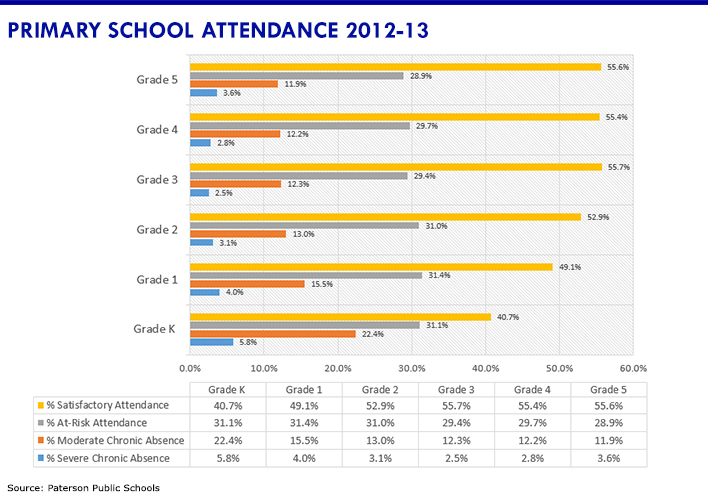

During elementary school years chronic absenteeism stabilizes but with a large number of students being on the borderline. Roughly 30-percent of students in kindergarten through eighth grades fall into what is called “at-risk attendance,” making them very likely to become chronically absent.

In kindergarten 28-percent of students are chronically absent with 31-percent being at risk and another 41-percent managing to attend regularly. “It’s a problem as early as kindergarten and pre-k,” said Chang. The national absenteeism rate is half that of the city. “Nationally we know it’s about 10-15 percent,” said Chang.

Chronic absenteeism declines slowly during the elementary school years prior to sky rocketing during high school. In first grade about 20-percent of students are chronically absent; in the second grade 16-percent; in the third grade slightly less than 15-percent; in the fourth grade exactly 15-percent; in the fifth grade exactly 15-percent of students are chronically absent; in the sixth grade the percentage moves upwards to slightly under 17-percent; in the seventh grade the rise continues with 18-percent; in the eighth grade absenteeism reaches almost 20-percent auguring much higher rates in high school.

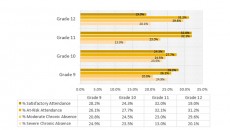

In high school the problem exacerbates resulting in almost half of the students being chronically absent. In ninth grade the percentage spikes to almost 46-percent; in the 10th grade that number climbs up to 48-percent, before retreating in the 11th grade. In the 11th grade absenteeism falls to 36-percent, before doing one final jump. In the 12th grade the percentage jumps to roughly 50-percent.

“We know this is a red alert that you are headed for academic trouble and not graduating from high school,” said Chang. The issue arises long before high school, said Chang, who cited a study that showed children who were chronically absent in kindergarten remained that way up to sixth grade and beyond.

Chart showing a big absenteeism problem in the city’s high school population during school year 2012-13.

Chang cites several causes for absenteeism: poverty, bad teacher, unsafe walking route to school, health issues, and discouraging parents. “There’s always chronic absence in the neighborhoods that have the highest level of asthma,” said Chang. “Sometimes families get worried: is my kid safe in school if they have an asthma attack?”

Sometimes distance is an issue, said Chang, and other times even shorter distances are a problem because the route to school may be dangerous and unsafe. Walking routes can be made safe by organizing a walking school bus, as other cities have done, said Chang.

At times students fear being in class, and fake illness to avoid school. She cites a story a parent told her at a school: “You know what happened in that classroom? They got a bully. Teacher can’t control the bully. All of the other kids call in sick because they’re scared.”

Rosie Grant, director of Paterson Education Fund, an advocacy, said chronic absenteeism is a big problem in the district that needs to be resolved. “If the kids aren’t there they’re not learning, so every day, every day matters,” said Grant.

“Poor performance schools have the highest absenteeism,” said Linda Reid, head of the Parent Education Organizing Council. Reid pointed out that a lot of families move around, and with the transitionary nature of the city, addressing the attendance issue presents a challenge.

“We’ve seen chronic absence get turned around,” said Chang.

Correction: Susan Peron’s name was misspelled as Susana Parone — article has been amended.