“There is no doubt as to the place to search. Often the searcher wishes the rocks could speak and tell the story of the happenings which once took place under their hospitable roof. But, alas, all he can do is to draw his conclusions more or less correct from the meager evidence extant, aided, though he be, in his conjectures by the insight born of long experience.” —Max Schrabisch (Bulletin 13, 1915: 20)

Mr. Max Schrabisch is considered hands down the Premier Pioneer Archeologist of his time here in Paterson. He was born in Germany on March 1, 1869 and left the places he loved on October 27, 1949. Ironically we both lived at one time on Hamilton Avenue.

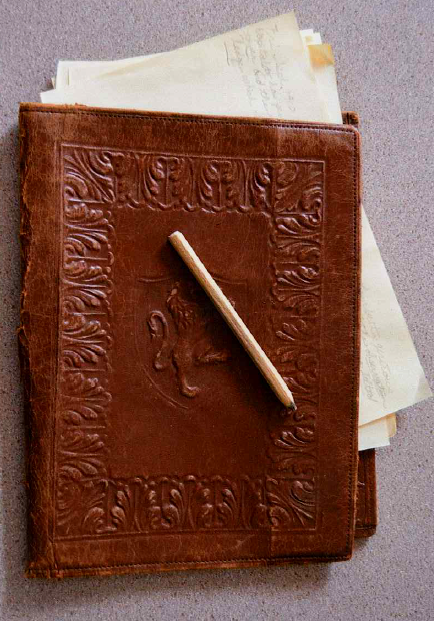

The leather sleeve in our photo is a circa third quarter 19th century item discovered on Lower Straight Street in 1974 by the author.

Photo by: Katey Dnistrian

I enjoy correspondences, but as one of those “Cave Man” types who happens to be computer illiterate by choice, it has its drawbacks. I admit though nothing thrills me more than to receive a “nice juicy letter.” I guess the sound of tearing open the envelope ignites that carnal instinct we humans suppress that wants us to literally tear into the next “telemarketer” who calls in the middle of the night trying desperately to sell us something we can’t do without. Who knows?

I received a letter recently in response to my article in the Paterson Times 11/18/2014 entitled “So It’s Just a Shoebox” that I took interest in. It reads in part: “…I liked the story and how you put the situation together, but I was left wanting to know a bit more. Thank you. Barbara from Nutley, New Jersey.”

So with this request in mind I’ve decided the best way to re-enter into the results of my experience on that dramatic day would be to start with a statement made by Max Schrabisch: “What is all the collecting worth when the collector never writes a word to contribute to the knowledge of Archeology?”

Traveling back to where I left off in 1965. Here I am standing at the front entrance of the Paterson Technical and Vocational High School and looking to my right a short distance away I can see this neat old fashioned red brick building with a sign that reads “Paterson Museum.”

Now this place possessed that unique character that a museum should have crammed up with really great stuff from town which I visited many times over.

Well just around the corner on Broadway was, “Lo and Behold” the Paterson Free Public Library. Can you imagine all the logistical support I would need for my future goals right at my fingertips. It happened to be at the public library that I was formally introduced to Mr. Max Schrabisch through his writings that would develop into an intimate personal friendship in spirit of course over these many years.

I became his captive audience totally immersed in his casual style of reporting.

It was simple, informative and possessed that turn of the century eloquence in composition which draws the reader into actually believing that they entered into another place and time. It’s a special talent anyone would have to admire.

Max Schrabisch began his career as early as 1896 and he continued to explore those secret places occupied by the first Americans here in Paterson long before any formal state sponsored efforts to do so, recording archaeological sites throughout the tristate region. Unfortunately, those site reports could only mention the specific location. Interest in the preservation of Native objects was realized too late. But his passion would bring him to discover new places to document, such as Rock Shelters. To satisfy the curiosity of those of you out there who are unfamiliar with this term “Rock Shelter,” they are natural rock formations (overhangs) that allow an individual to sit or stand under.

So with a slice of that good old fashioned Pioneer spirit and the urge to explore, I did a bit of experimenting and actually camped overnight in two of these fascinating places with the idea of possibly recapturing ancient cultural habits on site. The experience was absolutely awesome which reminds me of an old but true phrase: experience is the best teacher.

I’ve visited quite a few of the Schrabisch sites over these many years. To me, they are those hidden and mysterious places once occupied by the red shadows of the forest that we hikers pass by on a trip through the “Jersey Highlands” on a brisk fall day. One in particular on Federal Hill is a site formally known as “Pompton Junction,” a forgotten place hidden through time and off the beaten path that I would like to share with all of you. So sit back and relax, kick off your shoes and let your imagination drift away.

“Federal Hill looms dark and grim, a tumbled and broken region, stimulating in its wildness. Perpendicular cliffs, torn and cleft by the upheavals of Nature, tower above the lower portion of the hill, which in turn is bestrewn with cyclopean boulders and covered with a tangled growth of underbrush. The jagged hillside abounds in crags and fissures and gigantic rocks are piled up on top of each other, as if placed there by beings gifted with inconceivable strength.” (Schrabisch, Max. “Indian Rock-Shelters in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York.” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. III, 1909: 144)

Now, you can’t deny his descriptive abilities here, especially by the use of mystical characters whose inconceivable strength placed a mosaic of cyclopean boulders along the lower portion of the hill. It’s almost as if he wrote the opening visual sequence in the movie “Raiders of the Lost Ark” when archaeologist explorer Indiana Jones journeys into the unknown and discovers the darkened opening of a mysterious cave buried deep in the forest. But wait, there’s more. In a few paragraphs further on, he purposely delivers a meltdown blow to your imagination in the clever use of the phrase “Indian Troglodyte” which compels the reader to seek out the nearest dictionary for its meaning. It’s simply great writing that stimulates curiosity in the otherwise boring scientific reporting.

Some years ago while I was re-examining one of my favorite Max Schrabisch away to another time and another place, I envisioned for a moment a man seated close by. He wore soiled clothes. His face gave the impression he was exhausted from work. He held a lead pencil in his hand that he tapped slowly against a stone. Lying on a large rock before him was an old fashioned leather sleeve filled with papers faded with age.

He sat there motionless just staring out as if he were thinking. Below him was “Paterson City” stretching out in all directions. To his left was “High Mountain” which formed a striking feature in the landscape dominating the hills to the North, and to his right tucked away beyond his vision was the “Great Notch,” a massive basaltic rift that separates itself from the main ridge of “Wach-unk Mountain,” forming a natural corridor to the east and west. These were familiar places to him because they were a part of himself.

I could see his image as if he was actually there, and as I looked closer, he raised his head slowly and glanced at the enormous block of stone balanced above him and began to write:

“To one fond of prying into the mysteries of the past the exploration of an aboriginal rock shelter is a most fascinating undertaking. To such a one these places are invested with an irresistible charm, for it is here, on the well-defined space underneath the rock, that he fancies to come nearer to the Redman and to enter into greater intimacy with him.” (Schrabisch, Max. “Indian Habitations in Sussex County, New Jersey.” Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin 13, 1915: 20).

This story was contributed by Matthew Cooley on behalf of Stephan Woll. Woll is the Former Resident Archeologist for the Basket Historical Society in Long Eddy, New York.